Over the last several months, Brea Olinda Unified School District (BOUSD) has been heavily engaged in anticipating how the projected state budget deficit will impact the district’s local decision-making. With a projected deficit falling between $37 billion to an excess of $73 billion, under Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget plan, combined with the District’s responsibility under AB1200 for BOUSD to submit a three-year positive budget to the County Office of Education, the unpredictable nature of the state budget has made budget planning more difficult than ever.

This article is intended to help the community understand how schools receive funding in California and some of the challenges BOUSD faces in anticipation of reduced funding.

As reported in a recent Orange County Department of Education article, which addresses the state’s budget and its impact on school districts across OC, “many school districts [like BOUSD] are grappling with a number of fiscal challenges like inflation, the expiration of COVID-19 funding and declining enrollment, particularly in areas like Orange County, where birth rates have dropped and soaring housing costs have made it difficult for many families to buy a home.” Gov. Newsom’s budget is also projecting a much smaller cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) than in previous years, which further exacerbates the District’s budget challenges. The COLA will go from 3.9 percent to a projected 0.76 percent, over a 3 percent decline in revenue.

For those who are new to understanding how schools are funded in California, the easiest way to simplify it is - all districts receive a combination of state and federal funding, which essentially means that if the state projects a loss of revenue, so must school districts, because the decline in revenue at the state level has a direct impact on the amount of funding received at the district level. Furthermore, each district in California receives different levels of funding based on a number of factors and due to the state’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF).

“Most of the time, budget assumptions can be predictable, but when the state's projection shows a wide loss of revenue gap for the upcoming fiscal year, the next two budget years will be equally complicated due to a number of factors. That makes our work at the district level more difficult.” said Assistant Superintendent of Business Services Rick Champion.

“Ongoing expenditures such as salaries, instructional program costs, facilities maintenance and unfunded state programs, are just a few areas the district is trying to balance in terms of planning for the next three years.”

To help break down the BOUSD’s funding and budget even further, it is important to recognize how schools are funded in California.

How are schools funded in California?

Back in 1988, voters approved Proposition 98, which is a constitutional amendment that establishes an annual minimum funding level for the state’s K-12 schools and community colleges each fiscal year - the Prop. 98 guarantee.

The funding comes from a combination of state General Fund revenue and local property taxes to help support K-12 schools (including transitional kindergarten), community colleges, county offices of education, the state preschool program, and state agencies that provide direct K-14 instructional programs. The formula typically sets aside 40 percent of the state’s general fund budget, meaning that education gets more funds when the state’s economy is strong. It’s also important to note that while Prop. 98 establishes a required minimum funding level for programs falling under the guarantee as a whole, it does not protect individual programs from reduction or elimination.

How is the Prop. 98 minimum funding guarantee calculated?

Each year’s Prop. 98 guarantee is calculated based on a percentage of state General Fund revenues or the prior year guarantee adjusted for K-12 attendance and an inflation measure. Since some of this information is not available until after the end of the state’s fiscal year, the Legislature funds Prop. 98 at the time of the annual Budget Act based on estimates of the Prop. 98 minimum funding level.

What about COLA? If every school district receives a cost of living adjustment, doesn’t that help address Brea Olinda’s budget?

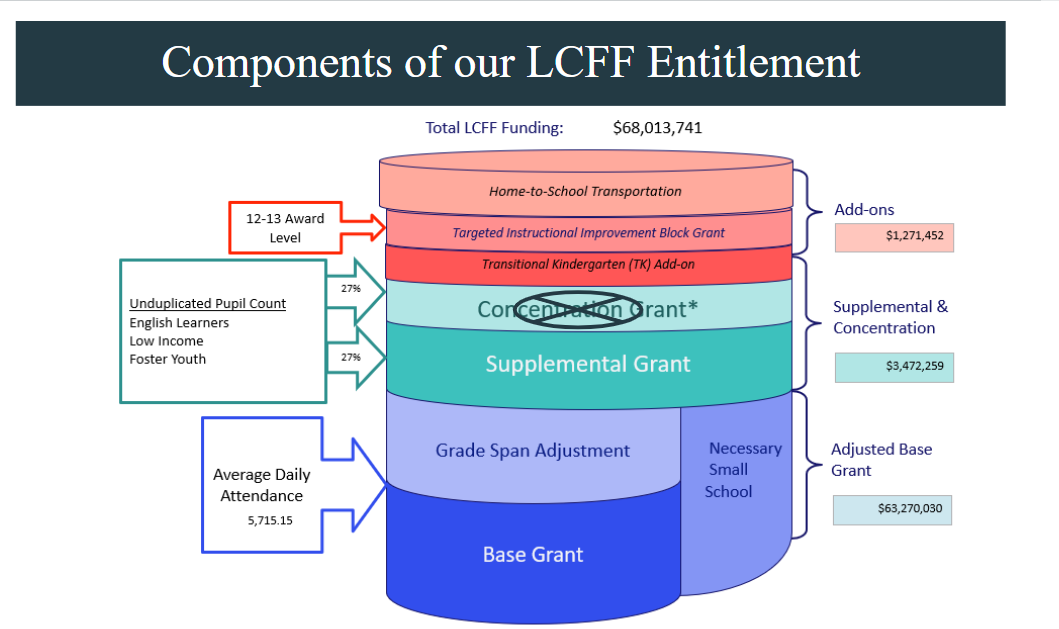

Not exactly. While it may be true that every school district in California will get the same COLA percentage from the state, not every district is funded the same. One example is the state’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The LCFF was designed to channel more money to districts that have students experiencing the greatest needs, such as English language learners, foster youth, and students from low-income families.

So, while the COLA will help the District’s budget somewhat, BOUSD must still make decisions based on the projected LCFF funding. BOUSD’s LCFF funding is much lower than that of districts because BOUSD does not have a high percentage of English learners, foster youth, or low-income families.

In addition, schools and districts in places where absenteeism is up or where enrollment has declined more significantly might be facing bigger shortfalls because funding is tied to average daily attendance, or ADA. In other districts where property tax revenue exceeds the amount of funding they would get through the state’s formula — these are known as basic aid districts — schools get to keep those extra dollars. But that doesn’t apply to BOUSD. Brea Olinda is funded based on our enrollment multiplied by our attendance rate. See figure below.

When all of those funding sources mentioned above all come together to support Brea Olinda’s budget, the fact remains that BOUSD will continue to be the lowest funded district in Orange County due to a number of factors including:

- Lower state revenues

- Projected reduced COLA

- Declining enrollment

- Average daily attendance

- Increased pension costs

- Unfunded state program costs

Generally speaking, what are the impacts school districts face as a result of the state budget?

With state revenues down for a variety of reasons including the fact that less money was collected from personal income, sales and corporate taxes, California faces a long road ahead when it comes to reaching a balanced budget.

The main reason is said to be capital gains taxes from higher income earners, which have been delayed. The other looming issue was that the revenue couldn’t be tracked as usual since the tax payment deadline was extended last year to help those impacted by natural disasters. This made the state unaware of how much revenue was actually missing.

With all of these factors, districts can’t quite anticipate what the budget will look like, let alone be able to plan for the current year and next two years. In January, the Department of Finance Report indicated that revenues were down $5.9 billion from original budget assumptions in the current year. But since January, the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) predicts the gap has widened even more, forcing many districts to take a more conservative approach to preserving their budgets.

How will the state address the gap?

Gov. Newsom wants to rely on a number of strategies to close the gap, which, again, is somewhere between $37 billion and $73 billion. His plan includes tapping into the state’s reserves — that’s essentially a savings account that was created for times like this — along with reducing expenditures and borrowing internally. He also wants to delay and defer some payments until things improve.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office, or LAO, suggests pursuing alternative savings and immediate solutions to avoid future deficits. The office advocates for using reserve funds to cover the 2022-23 shortfall and urges the Legislature to reject one-time spending increases and review unallocated funds for possible reductions. In addition, the LAO suggests zeroing out cost-of-living adjustments and most other ongoing spending increases. The LAO says it would prioritize core school programs and promote budget stability.

What can BOUSD parents and community members do to support budget planning?

Local families and community partners play a significant role in the development of school budgets through their participation and feedback. Attending school board meetings and public hearings is a great way to stay updated, share perspectives and ensure funding and policy decisions are transparent. Additionally, every district must annually update its Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) which identifies funding priorities. The process of updating the LCAP requires gathering input from students, staff, parents and community members. The LCAP is a structured way to gather the voice of the community.

Lastly, it’s essential that parents and community members stay engaged with local legislators who will prioritize the needs of school districts and the community. Listed below are the names of Brea Olinda’s local and state legislators who can be contacted to urge support for school funding:

Doug Chafee, Orange County Board of Supervisors (714) 834-3440

Josh Newman, State Senator, 29th District (714) 525-2342

Bob Archuleta, State Senator, 30th District (562) 406-1001

Phillip Chen, State Assemblymember, 59th District (714) 529-5502

Tony Thurmond, State Superintendent of Public Instruction (916) 319-0800

Gavin Newsom, California Governor (916) 445-2841